A History of Storage Media: the Williams-Kilburn Tube

In the last post, we discussed the fairly ubiquitous punch card, a mechanical write-once mechanism. Punch cards were mostly used for data, though, and control programs were inputted through a complicated system of patch cords. Reprogamming these machines was a huge undertaking! To speed up this process, researchers proposed using easily replaceable storage mechanisms for storing both programs and data input.

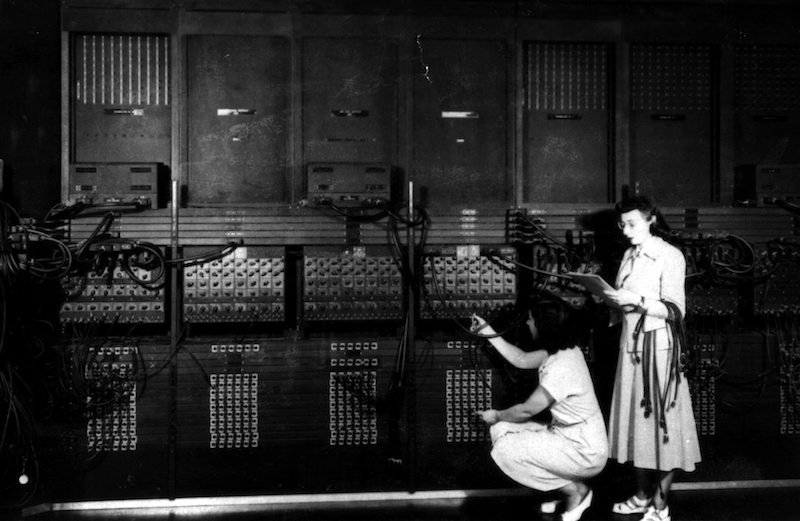

Two women wiring a portion of ENIAC with a new program. U.S. Army Photo.

While it’s possible to build computers using mechanical memory, most mechanical memory systems are slow and fiddly. Developing electronic memory was the next big frontier in computer design.

With the stage set, let’s pick up the story in Manchester (coincidentally, a city well-known for its textiles industry!) In the late 1940s, researchers at Manchester University developed the first electronic computer memory, essentially by cobbling together surplus World War II radar parts. By making a few ingenious modifications to a cathode ray tube, Frederic Williams' and Tom Kilburn’s lab at Manchester built the first truly reprogrammable computer.

An early history of cathode ray tubes

The first display cathode ray tube was invented just before the turn of the 20th century. These tubes were soon used widely as display units for oscilloscopes and other scientific instrumentation. Soon, cathode ray tubes became the defacto method of displaying electrical information.

During the Second World War, cathode ray tubes became ubiquitous in radar systems, which jump-started research into more advanced CRT technology. For example, researchers added delay lines into radar systems, so the systems could store and filter out out non-moving objects at ground level, like buildings and telephone poles.1 Non-moving objects on the ground always return the same signal at the same delay, so if a radar system had memory built in, it could look for and cancel out those obects. This way, a radar screen would only contain moving objects, so the operator would have much less clutter on their screen when looking out for enemy aircraft.

These early delay line systems were well-suited for conversion into computer memory. One branch of research adapted the delay lines as computer memory (which we’ll talk about next post!), and another investigated using the CRTs themselves to store data. A group at Bell Labs attempted to filter out non-moving objects by transferring data from one CRT to another.2 During a visit to the labs, Frederic C. Williams learned of this effort, and he and Tom Kilburn attempted to use the same CRT setup to store digital data. When Williams accepted a professorship at the University of Manchester, he brought both his CRT research and Tom Kilburn with him.

Secondary effects: principles of operation

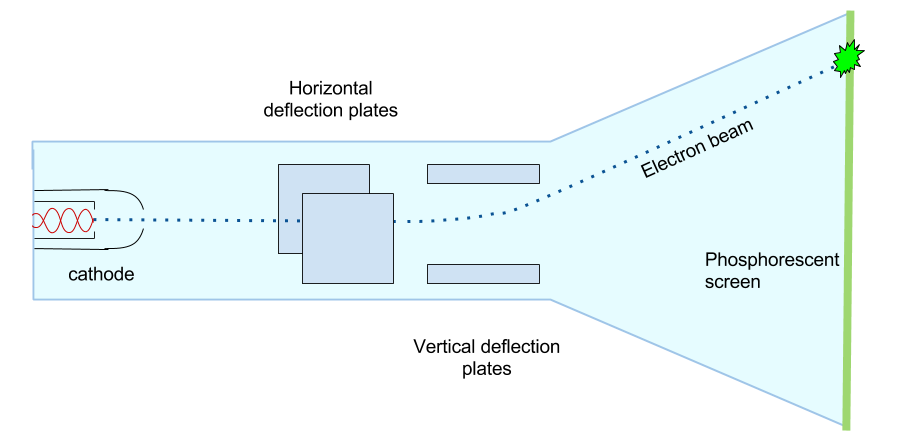

Backing up a moment to discuss how CRTs work – a conventional CRT displays an image by firing an electron beam at a phosphorescent screen. Two electrostatic plates (or magnets3) steer the beam around, scanning across the entire screen.

The brightness, color, and persistence of the scintillation depends on the type of phosphor on the screen. Depending on the phosphor and the energy of the electron beam, the bright spot lasts from microseconds to several seconds. During normal operation of a CRT, though, once written, the bright spot on the screen can’t be detected again electronically.

However, if you crank up the energy of the electron beam, the beam knocks a few electrons out of the phosphor, which is an effect called secondary emission. The electrons deposit a little distance away from the bright spot, leaving a little charged bullseye that persists for a little while.

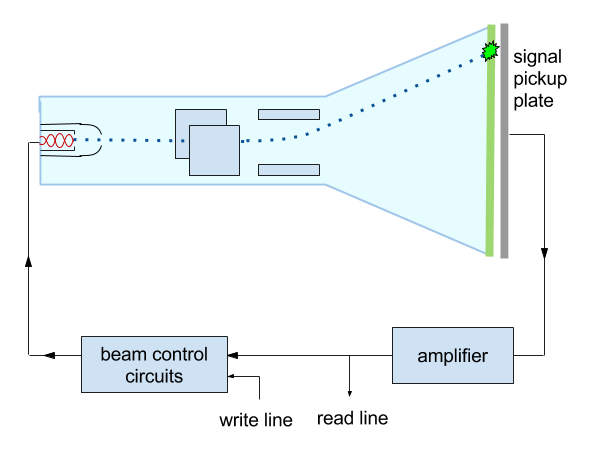

To read the data, the tube takes advantage of another secondary effect. When the electron beam hits the screen, the secondary emission of electrons induces a small voltage in any conductors near it. If you place a thin metal surface in front of the surface, the screen and the coating together serve as a capacitor, separated by the glass of the screen. Changes in voltage on the screen induce a change in the screen, as well.

To recap:

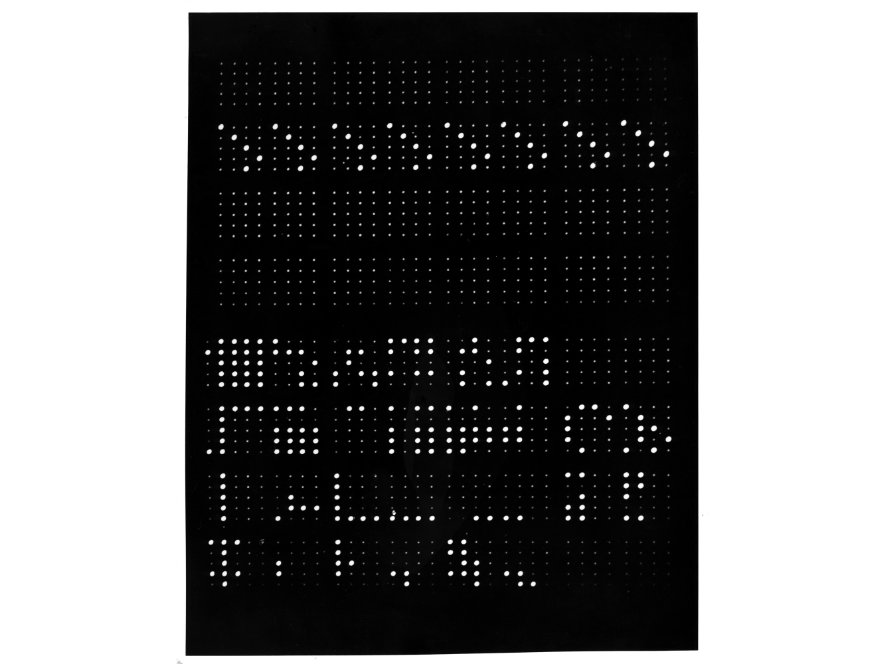

To write data, the electron beam sweeps across the face of the tube, turning on and off to represent the binary data. The little charged areas across the screen are essentially little charged/uncharged capacitors.

To read data, the electron beam again sweeps across the face of the tube, but stays on at a lower energy. If there were a 1 written there already, the point of positive charge on the screen gets neutralized, discharging the capacitor. The pickup screen thus sends a pulse of current. If there were a 0, no discharge occurs, and the pickup plate sees no pulse. By noting the pattern of current that comes through the pickup plate, you can determine what bit was stored in the register.4

Image courtesy the Computer History Museum.

Since the read is destructive, any read is followed by a write to the same location with the data just read. That said, the charged areas leak away over time, anyway, so a refresh/rewrite process is necessary. Modern DRAM has a similar memory refresh procedure, too!

The Williams tube was true random access memory – you could scan the electron beam to any point in the screen to access data near-instantly. Other forms of contemporary memory had to be sequentially accessed.

After Williams' visit to Bell Labs, where he observed researchers using these effects to transfer data between CRTs used in radar, he set out working on duplicating this work for digital data. When he came back to the TRE in 1946, Kilburn and Williams built a tube that succeeded in storing a single bit. When Williams and Kilburn moved to Manchester, they worked on developing a tube with slightly more storage capacity.

The Manchester Baby

After the team at Manchester had a working memory tube that stored 1024 bits, they wanted to test the system in a proof-of-concept computer. They had a tube that would store data written to it manually, at slow speeds, but they wanted to test that the whole system would still work when it was written to constantly, at electronic speeds. To demonstrate that the tube worked as computer memory, they built the Small Scale Experimental Machine (colloquially known as the Manchester Baby) as a test bed.

The Baby consisted of 4 CRTs –

- one for storing 32 32-bit words of RAM,

- one as an accumulator,

- one for storing programs,

- one for displaying the output or the contents of any of the other tubes.

Williams-Kilburn tubes are an unusually introspectable data storage device!

Programs were entered one word at a time, using a set of 32 switches. The first program run calculated factors for large numbers. Later, Turing later wrote a program that did long division (the Baby could only do subtraction and negation.) Thus, the first stored-program computer was built around a cathode ray tube!

Later history

Parts from the Manchester Baby were repurposed for the Manchester Mark 1, which was a larger and more functional stored-program computer. The Mark 1 developed into the Ferranti Mark 1, which was the first commercially available general-purpose computer.

The Williams-Kilburn tube was used as RAM and storage in a number of other early computers. The MANIAC computer, which did hydrogen bomb design calculations at Los Alamos, used 40 Williams-Kilburn tubes to store 1024 40-bit numbers.

Though the tubes played a large part in early computer history, they were quite difficult to maintain and run. They had to be tuned by hand frequently, and were eventually phased out in favor of core memory.

Other Resources

- A short video documentary on the Manchester Baby

- The Nature letter from Williams and Kilburn about the SSEM

- and the links in the footnotes below!

-

This Wikipedia section describes the motivation for canceling out ground echoes in radar systems in more detail. ↩︎

-

Kilburn wrote about Williams' visit to Bell Labs and the general development of the tube many years later. ↩︎

-

Oscilloscopes and Williams tubes use electrostatic plates, since they have a better frequency response, and so operate faster. The magnetic coils used in television CRTs present an inductive load, so they’re harder to drive at the high frequencies oscilloscopes use. On the other hand, televisions use magnetic deflection since the plates obstruct (and distort) the beam when the deflection angle is large, so magnetic deflection is better for large screens/short tube lengths. [themoreyouknow.gif] ↩︎

-

More information about the tube’s operation from a Naval training manual on digital computers! ↩︎